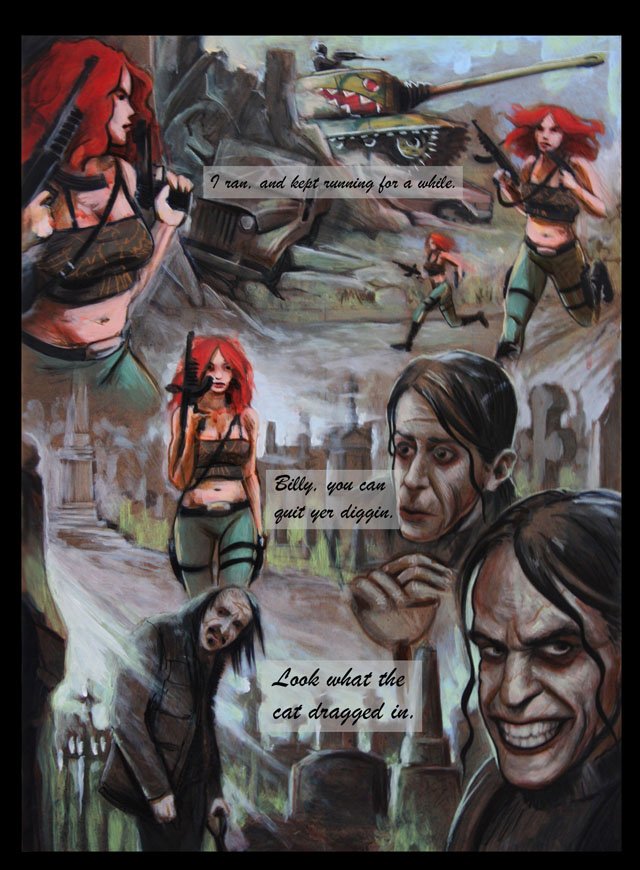

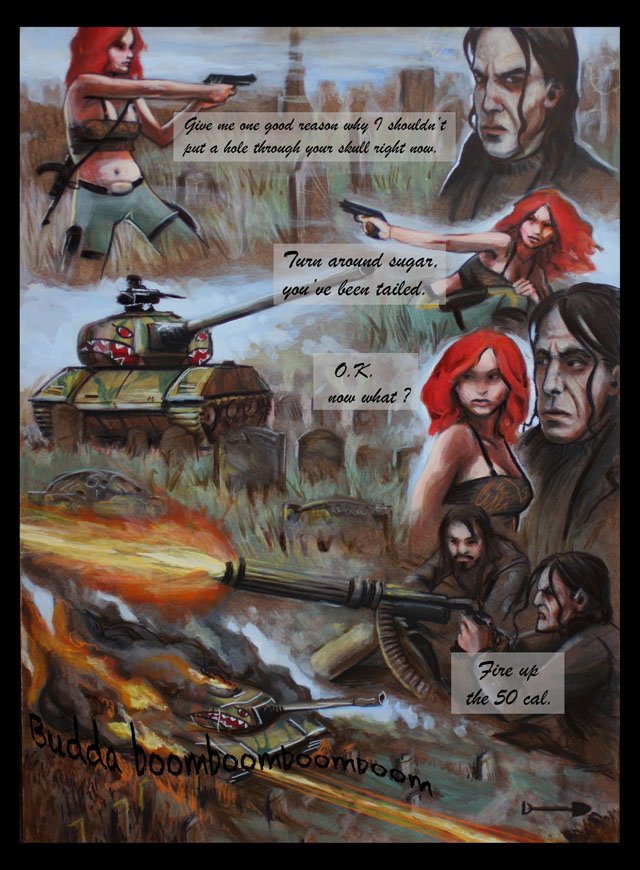

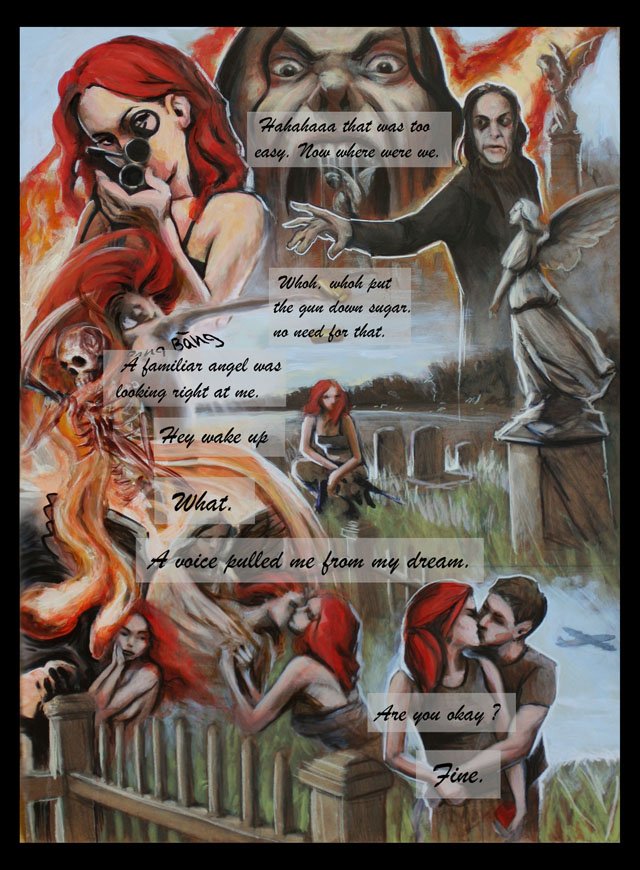

Summer Cottage from Hell

By Christopher Jon Luke Dowgin

Part of the Sinclair Narratives

4th of July 1909~Louie had just picked me up in my 1906 Stanley Steam Car from the bonfire on Lookout Hill. We were heading to Beverly to visit Roosevelt at his daughter Alice’s home. It was an experimental car that Arthur built at the General Electric plant in Lynn that could reach top speeds of 70 mph. Louie was always complaining he could not open her up around the curves heading north on Route 127. Eleonora was already causing havoc on the road and has become a regular at the district court in Salem.

“Hey, Boss! Why can’t I just let her stretch her legs a little?” Louie pleaded. Louie has been my oarsman and driver now for over 500 years, but he still does not believe me. Being immortal has some advantages over others. Most of my friends, with the exception of a few, die within normal spans of times for the average human. So it is not that Louie is another immortal, I just recognize him each time he is reincarnated. The good thing about true friends, we are pulled to each other in each life.

“Louie, you know we are going to the president’s daughter’s house, plus we are driving past the new president’s summer White House,” I said from behind the Salem Evening News, “Louie, have you heard that Evans has fallen from the house prior to Taft arriving at his summer cottage? He is not expected to survive the week. It says his wife is frantic with his fall only happening 3 days prior to the President’s arrival.”

“I prefer the reins of the steering wheel. Much safer in my opinion.” Louie spoke as if it was gospel.

As we were passing Ober Street on the way to the Evan’s estate on the Cove, the trolleys were on top of each other as pedestrians and a few horses blocked their way down the road. “Who cares about a portly president any ways! Give me our old friend any day!” Louie was going on, “I’m not embarrassed to say I bought one of those Teddy bears--and if anyone has anything to say about it I have a strong left to the nose with a bigger hammer in my right I might say!”

The crowd that normally crowded Dane Street Beach...and it seemed all points beyond, now were pushing and shoving their way toward the Evan’s residence to catch a sight of our new president who decided to move the White House and its staff here for the summer. I even had seen some of the Plummer Boys making their way through the crowd plying their trade and alleviating the wealthier set from the Farms from their overflowing wealth.

Let me not mislead you, Beverly Farms is not a poor farming community. I believe none of them would know the back end from the front end of a cow; it was a breeding ground for the wealthiest and most influential sort in the country. Which explains Taft’s choice for his summer residence.

Louie got fed up. He drove through the yard on the opposite side of the street from Ober, went around the house and came out 3 houses up back onto Route 127. Then he floored it all the way up to East Corning and was forced to slam on his brakes as the crowd spewed out from Corning Street. We made a total advance of 5 houses. While I sat in the back and Louie just cursed and waved his fist at the crowd I read further about Evan’s recent history. His American Rubber Company had just received a contract with the Wright Brothers to make tires for their planes. In another article there was a follow up of America’s possible pull out of Cuba on the heels of Panama breaking from Columbia. I wondered if we were pulling troops out of Cuba to redeploy them. Something Col. House might know about.

The crowd broke up as the police finally arrived and made way for the Trolley coming from Manchester heading south to make its way. The police were overtaxed from the various holiday celebrations in the different neighborhoods of Beverly, but if the Farms were where the lords lived, Manchester was where the Rajas and Czars of our nation controlled everything from. There was always police on hand for this crowd and their whims. Plus I thought I had seen a few Pinkertons amongst them breaking up the crowd with some heavy persuasion. Louie just jumped onto the tracks and ran behind the trolley through the gap in the crowd and ran the Stanley up to 72 miles around the tight curves forcing me to rip my paper and slide to and fro, front and back. I would have spoken out, but I know my efforts would of been all in vain.

___

We arrived at Alice’s stone home on the ocean and were met by Teddy in front of the house playing with her Wolfhounds. He just got off the ground from wrestling the larger of the two, Jameson. He brushed off his clothes and made his way for us with a grand bully greeting! Teddy had taken a break from the party that was happening in the back yard. Remond’s descendants were catering, a family business that dates back to the prior century. Charles Remond had been Frederick Douglass’ mentor on the abolitionist lecture circuit whose father started the business.

“Good to see you Henry! Come Louie park the car and join us in the back; Alice’s friend from Manhattan remembers you from the last Bacchanalian party here.” Teddy pauses and says a little withdrawn, “I just learned to let my daughter’s stories and some of her friends’ go in one ear and out the other. While I was president I could only handle her or the country; I chose the country and now I am forced to handle her. Begrudgingly though, I must add.” Teddy then grabbed my hand with a firm, but a little too much, grasp to exaggerate his stout frame and slapped me on the back with a huge toothy smile, filled with warmth, and guided me to the back.

Amidst the party goers we headed to Frank Crowninshield. Frank was better known by his friends as Keno. He had hailed from the illustrious smuggling family from Salem that bred their way to a shared fortune, which created the first millionaires in the country. Keno was one of Teddy’s Rough Riders from Cuba. So naturally once Teddy arrived again they began talking about the current state of Cuba. Teddy tried to avoid the subject, I believe he was trying to manipulate Taft and his cabinet to support the Panamanian rebels. Keno tried pushing the subject and started recalling their adventures in Cuba, when Nikola Tesla entered the conversation with his east European softness. The conversation seemed to drift to other subjects.

“Hello Henry. When will you let me study that stone of yours and its electrical properties?”

“Nikola, I would soon enough let you see Moses’ capacitor than let you see the Philosopher’s Stone.” These were some of the treasures I brought from my family’s Templar confines within Scotland to Salem a 100 years before that Italian with his Spanish crew. The Sinclair’s guarded these treasures, since de Molay’s death, at Roslyn, Scotland. I just brought the important stuff here to hide in my tunnels and the Chapel that keeps moving under the rose bushes in Salem. Tesla has of late been working on radio technologies, free supply of electricity, weather control, and a death ray to end all wars… “Is the weather to your liking today, or will you change it?”

Nikola laughed and handed me a champagne. I do wish it was a chocolate milk. “I’m sorry Henry; you just missed our friend Mr. Clemens. He said to pass on his greetings, but he went out to the sea to see the latest steamboat.” Not too long ago Samuel sent me a copy of his latest short fiction which involved the Hammonds in South Africa by what Tesla called a facsimile machine.

Alice came around the corner and took my champagne from behind and handed me a chocolate milk as she rounded to my front with a smile. “Hello Alice. You are looking as risque as usual...”

“Why thank you Henry, you rake.” This is when Teddy grabbed me by the elbow and led me to the smoking room. I just smiled over my shoulder as Alice waved back at me with a seductive grin and a laugh as she just shook her head.

___

Teddy led me and Keno to the smoking room. Nikola went to join Samuel at the boat. He said something about electric dynamos powering the boat if he could make sure they would keep dry or something. The room was filled with trophies on the wall: gazelles, rhinos, elk, caribou, and more. There was an elephant foot that held a stretched piece of an African elephant ear over wood for the table. A fist of a silver back gorilla holding up an ottoman. These were the overflow items of his home he forced his daughter to take in after bribing Col. Mann to keep her latest exploit out of his Manhattan social papers. He used this room to still impress and control the wealthy power brokers on the North Shore along this Gold Coast.

“Henry I see you have your chocolate milk; Keno a scotch?” Keno shook his head and took the rocks glass with ice. Now we noticed that we had disturbed Louie and that madam he had met prior laid out on the lion skin on the floor. The woman did not bother dressing and just winked at him over her shoulder and departed. Louie was quite embarrassed, as he only found time to unbutton his pants which he was fixing now at this moment. “Louie, stay. This will pertain to you as well. For I know you venture on many of Henry’s exploits and you will be a great hand at our latest endeavor I will propose now.”

The three of us took our seats in Alice’s nailhead leather chairs. “Now I fear Taft is about to dismantle my presidency. He is resisting my calls for moving the troops from Cuba to Panama to back the building of my canal.”

“But Ted, all we fought for in Cuba! How can you!” Keno protested.

“Keno, you know better than me that we all almost got killed charging San Juan Hill. I never have been a good leader of troops in small battalions. I proved better at bigger maneuvers of whole armies and a nation they derived from,” Teddy said as he placed his hand on his old comrades shoulder. “It is time for the canal, but Taft is trying to block it.”

At this time Nick, Alice’s husband enters the room. He has been recently dismantling Roosevelt’s Square Deal from his seat in Congress. Teddy fought all of those years to make sure children, women, and men have a fair deal to employment and wages. It seems Taft’s Yale roots were showing now. It was his father and William Russell who founded the Skull & Bones at that university. From there they continued the Federalists and Whig plans of servitude of this nation’s poor in service of their English masters. Teddy got quiet and then went into a Bully rage and kicked his son-in-law out of a room in his own house. Granted, Teddy did buy this home for his daughter.

“I believe the little he has heard will definitely make its way to Taft’s ear. Taft has not been himself for quite sometime. The weirdest thing is he has even changed the hand he writes with. Just before I left the White House, many papers had to be taken back to him to sign in front of other cabinet members.”

“How is Nellie doing? I have heard she has suffered a stroke and has not arisen yet.” Keno inquired about his old friend’s wife.

“Little word has been heard, but she has not travelled with her husband to the Evan’s and remains home in her bed.”

“That is strange, my cousin had just seen her at Kellogg’s basking in his gruel, that he calls healthy, and bathing in the mineral springs all pink and in good health.” Keno said scratching his chin.

“My intelligences have heard that there might be foul play upon Robert’s fall from the horse. Some of Taft’s bodyguards are not all from D.C. Some come from the Pinkertons. In fact those personally hired by Frick. They are quartered at his Eagle’s Nest in the Farms. There are suspicions that the horse was doped.” Teddy explains as he takes his seat with his scotch.

Now Alice, enters and takes his glass and replaces it with a chocolate milk. “Dad, you know what the doctor said.”

Teddy just looked gruff, but acquiesced with a harumph. Then he just sat up with a bolt with his chocolate milk out in front, “Plus Taft is fighting to keep the troops in Cuba.”

In time after some more conversations on more personal notes between four old friends and after Nikola joined us once again the night just waned on and we found ourselves the only ones left at the party as Alice, had escorted everyone to the door hours ago. That is what happens when good friends are joined together; time is lost, but made at the same time. Times to be remembered years down the road.

As Teddy led me out with his arm around my shoulders once more he looked at me, “You know Henry, I like your choice of drink. I just had Alice make that excuse about the doctor to save face and pretend to force this lovely concoction on me.” Teddy gave a little shrug of who cares and continued, “Now join me at the Evan’s summer cottage to meet the president on Wednesday. Then tell me your opinion on these matters we discussed tonight and I will reveal more that I know.”

___

Teddy had me picked up in his Packard Electrics car, him driving with Nikola at his side. I got into the back. He sped up English Street and squealed the wheels, almost flipping us, onto Webb Street. We went past Collins Cove to avoid the Hood milk wagons at this hour on the interior sections of Bridge Street, but we got onto Bridge Street later from Planters. Lucky for us, the drawbridge was down and we took the next right after the bridge to go past Dane Street Beach after a left up the hill. Then it was just another two rights, in quick succession, and we were on Ober. This time the trolley was not blocked, but pedestrians walked all over the road. Teddy had no patience and just sped through them casting many to the side. Some of Taft’s bodyguards tried to stop him, but they were forced to jump aside and make way for him.

We parked by the carriage house. As I exited the car, I noticed Mrs. Evans walking across the way for her driver. I paid my respects. “Thank you Henry, you are so kind. Look at this crowd!” said a woman who was at her wits end. Woodbury Point where she resided was strewn with strangers, mostly drunk, who were picnicking, cavorting, hooting and hollowing. Many came to catch a glimpse of the president, but most just came for the party atmosphere that descended on the property. Many took to ripping parts of her estate down and bringing them home as souvenirs. “I must swear, the saint my husband was, this is the worst decision he ever made while he was alive was agreeing to let Taft reside here and he is not even going to be around to bear the brunt of any of it,” she exclaimed, as one frantic and in a hurry.

As Teddy and I had watched Mrs. Evans enter her car and drive off, we went toward Taft’s residence as we left Nikola behind to examine Lucius Packard’s car. I had noticed him making subtle grunts and nods as he looked at various parts and heard the sounds of the car as Teddy drove us here.

Taft’s butler showed us into the parlor where Taft was in conference with Frick. I kept my composure. I never warmed up to Henry. Frick came in like a barnstormer and took over the Farms. I never cared for him, but ever since he hired the Pinkertons to kill labor protestors at the Homestead Massacre, I despised him. I remember Carnegie just washed his hands of the affairs. He let Frick handle his workers as he saw fit and just went to Scotland to play golf. Then his negligence at the South Fork Damn and the Johnstown Flood… Don’t get me going…

“Hello Teddy. Sinclair. Who is your friend here?” Taft asked looking at Nikola.

“Taft, this is my old friend from Serbia, Nikola Tesla the eminent inventor,” I answered.

“Pleasure sir. Now join me in the drawing room where I have some light refreshments laid out for us.”

We followed him and Frick into the room. I was the last to enter. I would never have wanted Frick behind me at anytime. Nikola, as he walked in went toward the library and started observing titles on the shelf. He was an old advocate that the only true way to get to know someone is by the books in their study versus those they have for show in the library. These are the books they draw on the most.

The conversation relied mostly on Taft and Teddy going over tales from the White House and the personalities within and from all over the world. The mood changed as Taft recalled Teddy being thrown by a Ninjutsu expert. Teddy became Gruff and he turned the subject to Cuba.

“Why won’t you pull the troops!” Teddy blurted, “They are needed in Panama!”

“Now Teddy, lets not boor our compatriots today. Plus this will not end friendly.”

Taft’s butler handed Teddy a scotch and he settled on a stiff snort of it. Probably mostly in disgust that it was not chocolate milk. Henry never took his cold stare off me. Henry Clay Frick reminded me of Stephen White who I dealt with years ago within the Joseph White murder case in Salem. White had at one time controlled John Quincy Adams as he ran for his second term, His brother-in-law Joseph Story in the Supreme Court, Daniel Webster whose son was married to his daughter, and the prestigious Henry Clay. To cap it all off he controlled the national bank at the time. Frick’s stare was as steely as the steel Carnegie and he had made. Very similar to White’s stare. Frick began talking; I just zoned out in disgust.

Teddy slapped me on the back of the head to break my stare and I heard Taft, “You all must join me on the course tomorrow at the Essex Country Club.” Teddy agreed for all us as Nikola slammed the last book he was looking at and placed it on Taft’s desk on purpose without returning it to where he found it and filled out behind me and the president.

We got back in Teddy’s car and we went our way slowly up Ober Street. We did not make it far through the fray before a woman collapsed into our tire. Teddy was the first to get out, followed by Tesla who was closest to her to help. She seemed to be in a daze. Her clothes were a strew, just thrown on hanging from her shoulders with some vital areas exposed. I have not seen anyone so much in a state since the ghost on Derby Street that possessed a woman deep in her cups to save her sister that was dying of an opium overdose in the alley next to the Derby House. That was another life time ago, for most people...

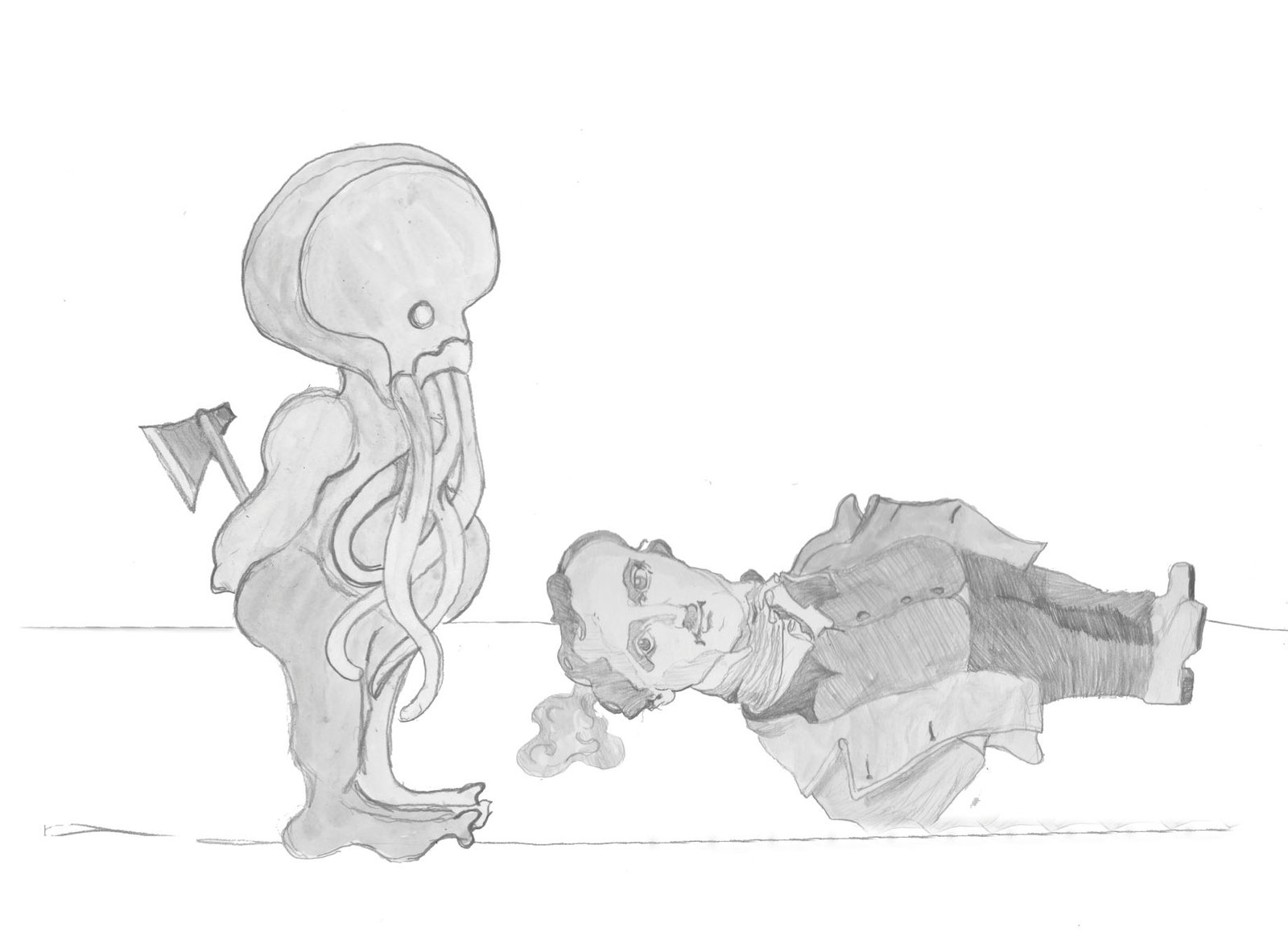

“Stay away from here! Bad things have happened! They are still happening. The Shoggoths are coming out of their frozen expanse. My body has been penetrated by things that bend the mind. Formless things. Arcane rituals. You must leave this place.” She just broke free and ran off into the crowd and we lost her.

___

I had Louie drive me to golf. I met Tesla, Teddy, and Taft at the second hole. With them was Frederick Ayers and the Hammonds. Ayers made a small fortune in patent medicine, but raked it all in on textiles in Lawrence. We were one short for me to join in for pairs, so I just joined for the walk. I always thought there was a better game to be played with a stick, two balls and a hole...Ayers played with Taft. Tesla showed as much agitation as I showed with Frick the other day.

Clemens had introduced Nikola to the Hammonds a few years ago. There was talk about starting the Tesla-Hammond Wireless Electric Company, but nothing came of it besides a few seances and some experiments in psychic powers. In fact John Hays Hammond Jr., the son of the pair, would steal some expired patents in radio technology in the future. It was bad enough Marconi just won the Nobel Peace Prize for stealing some radio technologies from Nikola this very year.

“You Can Not Reanimate the Flesh!” Nikola was in a furry.

“You heard for yourself at our estate incorporeal souls speaking to you. The intelligence can be moved from one vessel to another; for that is merely what the flesh is.” John Jr. was arguing with our friend.

“Yes, but the flesh will not rise again.”

“The ancient Chinese through acupuncture have proven a thousand years ago that electricity governs the movements and the health of the body. There is no reason after a silent death of the heart as it stills without a traumatic accident crippling the muscle and nerves that another bolt would not animate the body once more right after. Then add a consciousness once more to guide it.” Hammond said in utter confidence as if he were giving a lecture to a silent class. “In fact many of our elderly on the Gold Coast here would pay dearly for a younger vessel to have their soul transferred to.”

“That is sacrilege. I have been caught at many of your orgies of the flesh, which I quite enjoyed with the elite of Broadway on tour, but the calling on the Younger Ones and your sacrifices on the ocean, I can never partake on again for on those nights, I clasped my breast tight to prevent my own soul from being stolen.”

“You know West, was right. You felt it. You have seen it. Herbert reanimated the flesh several times, granted only the boxer lived.”

“Yes he is in Arkham Asylum now after he got caught during his cannibalistic killing spree. His brain was bashed in before death and the Doctor’s brain was dead too long before reanimation.”

“Though you just said it, the physical machines were broken. Those brains, the vessels that the soul resides in were damaged. If we can keep the machines in top shape before and after reanimation it will work. Then we apply the right current of electricity...”

At this moment a man on a horse gallops in and interjects, “Herbert West. Fine doctor. I served with him at West Point. Not much of a cavalryman, I must say,” the man is cut short as his horse rises up and throws him. John Hays Hammond Sr. spooked him by brandishing a golf club from his bag.

“You have to forgive my future son-in-law; he is a bit of a klutz, but he has a fine head. Graduated top of his class at West Point and is a potential team member of the 1912 Olympics,” Ayers explains, “But still, a klutz. Gentleman this is George Patton.”

George Stands brushing off his pants and shakes my hand. “Glad to meat you sir.”

“Henry.” I say and the rest of the introductions go around. This brought an end to the debate and George joined me in pairs for the rest of the holes. We shared Teddy’s bag.

On the way out after a light lunch Tesla asked, “What do you know of the experience of Edward Derby and his wife, Asenath? Along with some texts on the Illuminati by Morse’s father and Rev Bentley locally? I had seen a volume by Adam Weishaupt, a manuscript that is in his own hand with William Russell’s inscription just within the cover on Taft’s shelves in his library. There was also a treaties on the strange happenings of Derby and his wife compiled by the Miskatonic University. Derby was also in Arkham Asylum?”

___

A few days later I get a telegraph on my old Page Machine. Only a few friends I know still use Charles’ machine still, even though it is a far more effective tool. Tesla is one who finds it better to transfer his various radio technologies through that machine. Much more adaptive for his needs than Morse’s. Plus JP Morgan listens in on all of the telegraph messages. Morgan and Tesla had a falling out 3 years ago after Tesla had to give up his tower in Long Island because Morgan crashed the market that Tesla invested in with the funds Morgan gave him to build the tower…

Dear Henry ~ Stop.

Meet me at Mme. Zaza, occultist and palmist in nearby shop to Mason

Lodge ~Stop.

Wednesday, 4pm ~ Stop.

Nikola ~ Stop.

So Thursday came and I met Nikola and Mme. Zaza. Instantaneously I recognized Lady Jude who worked with King Mumford all those years ago. She knew me. She was not immortal, but upon her birth all of her lives would come flooding in once she becomes conscious after the first few months of life. “Henry, good to see you. It has been almost thirty years. Why have you not found me sooner. Only a bridge blocked us.”

“I can ask you the same.”

“I see you have been introduced already. Thirty years? You do not look older than 20 my dear.” Tesla exclaimed looking Zaza up and down.

“No. From another time. Henry and I met originally in the Occident as I was an Egyptian on a caravan plying my goods. I helped him remove his mother and a troublesome pregnant wife from Canaan to Egypt to avoid prosecution some 2,000 years ago. Then I had seen them safely to Marseilles, France. I taught his daughter well, in time. So much so she became a queen of the Gypsies.”

Zaza was quite talented. She had followed Fredrick Douglass up from the south and hid in Salem. She was a fugitive slave who kept changing her name and making up new histories for herself. The Remonds had helped her with a few alias before she settled in New Orleans. There she became know as Marie Catherine Laveau, the Voodoo Queen.

“There is plenty of time for that later, but there is some strange goings-on at Woodbury Point. I have seen many High members of the Hiram Lodge get off the train here and take private cars there. All alumni of the Skull & Bones and descendants of the Hartford Convention. Many from the Bohemian Grove.”

“Ah, Bohemian Grove. Clemens has mentioned that place. He went for a few years when it was for writers and artists. He said it turned dark quick. He mentioned hearing tales of Frick and Carnegie planning the Homestead Massacre there and mocking the Johnstown Flood during the Ceremony of Cremation after he stopped going from friends. I believe some of the actors who partake in the Hammonds’ debauchery are also members of the Grove. I have been caught up in many a strange events when the green fairy grabbed me and I did not have my with all to leave during their dark ceremonies. I wish I had my wits about me enough to have left and saved my soul from those marks they have placed upon it.”

“I met some of those men before in Knob Hill. Some befriended Mark Hopkins.” I said with a head shrug. In this life by the population at large, I am Edward S. Searles who married Hopkins’ widow. Some say I married the woman who was 20 years my elder for her money. From her husband she received the 33rd largest fortune in American history. When she died 18 years ago, that fortune was mine. My most intimate friends still know me by Henry.

In this life as Edward I surpassed my old friend Elias Hasket Derby Sr. who is ranked 39th, but Frick, that bastard, is the 27th just a few million short of JP Morgan. I met the Hopkins when I was decorating their Knob Hill mansion in San Francisco. After Mark’s death, me and Mary used that fortune to travel Europe with the help of François-Bérenger Saunière. We retrieved many of the most potent and dangerous religious and magical items that made their way into private collections who’s owners would have used them for destructive means. Many chapels that had others, we found safe, we let them retain those items. Now the items we did capture are safe in my Chapel under Salem. That is also a story for another date. As well are the tales Lady Jude and myself have had through the many lives we have danced together.

So gold digger? If you know my true wealth, I would be a thousand times richer than John D. Rockefeller. Not only do I have some of the most priceless items from the last 4,000 years or so, but I have been quite frugal for the last 500 years or so with compounded interest and all…

I was the one who gave Hopkins the loan to build his Central Pacific Railroad that completed the First Transcontinental Railroad. The Gold Spike was some gold from Solomon’s Temple, blessed by the man himself.

My fiends who have been reincarnated countless times and times again, know me as Henry. You probably recognize your friends too.

Have you ever had a dream of a friend where his voice is the same, but he looks completely different, even though he carries himself with the same bearing, gate, and body language. In dreams we see the soul as we first met them all of those lives ago. In fact! I just recognized George Patton as someone I knew at the Siege Of Orleans. He was in the army of Henry V when they laid waste to Agincourt, but when he returned I was Henry d’ Anjou fighting alongside Joan d’ Arc. We won that time and we had a drink afterward where he was enamored with our French Boadicea.

Henry just seems to stick through the years…

Most of the Hopkins fortune I gave to the poor in Methuen and the factory workers of Lawrence, many who worked for Ayers.

“Henry, many women have disappeared from the Bennet Street Neighborhood. The police just believe they are in the throng of the people descending upon Mrs. Evans property. No one is looking for them besides their families,” Jude tells, “Many of the dark magicians from Salem and the spiritualists who have worked with the Hammonds on the Gold Coast have been flocking there too. I have been asked, for my powers are legendary, but I can not play with any of those dark powers. My karma, I have been rebuilding since my time in New Orleans where I strayed, quite a lot from the good path.”

“That fits with the woman who bumped into Teddy’s car. She said some horrible things are happening. Something about Shoggoths...” Nikola said confused and excited.

“Shoggoths. Shackleton revived them on his expedition to Antarctica. For some time on their journey they were possessed by these formless monsters who can take you over cell by cell. As they were starving to death and carried fine silverware and crystal goblets and fine linens to spread over their diner table; none of them brought survival supplies or food for days out from their ship. Story has it that the ship got stuck in the ice beforehand, but it actually got stuck after Ernest realized that half of his crew were this monster. They could not attempt to seize him till they regained some sense and returned to where the food was to recoup. When their bodies and minds were refreshed these monsters turned on him in the skins of his closest friends. He was the one who stranded the ship and did not radio, one of your early ones I believe Nikola, for help till he killed all of these fiends with those who remained human. One or two of his crew were the monsters in disguise who made it back to civilization. I fear by what Lady Jude is saying, they made it to our shores," I explained.

___

I have been asked to meet the widow Evans, as we finally begin to call her, at the main house. Louie drives me in with a pocket of nails and a necklace of garlic around his neck… The nails I believe is some magic Zaza had mentioned to him that will keep his soul nailed to his skin so another can not jump in it. Strange for Louie, he is quiet the whole trip and is actually driving slow in our Stanley. Too slow.

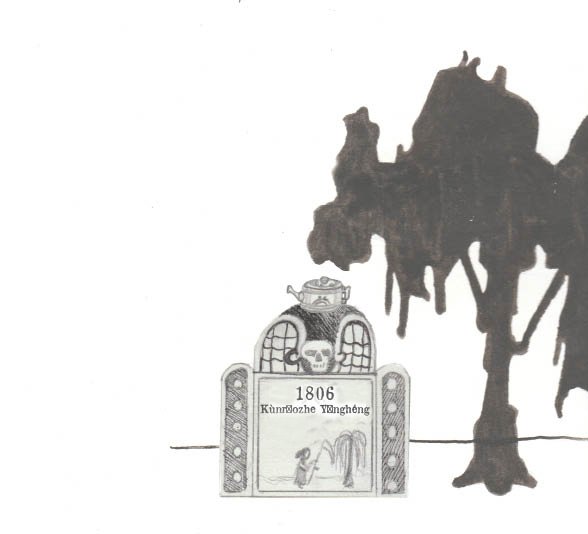

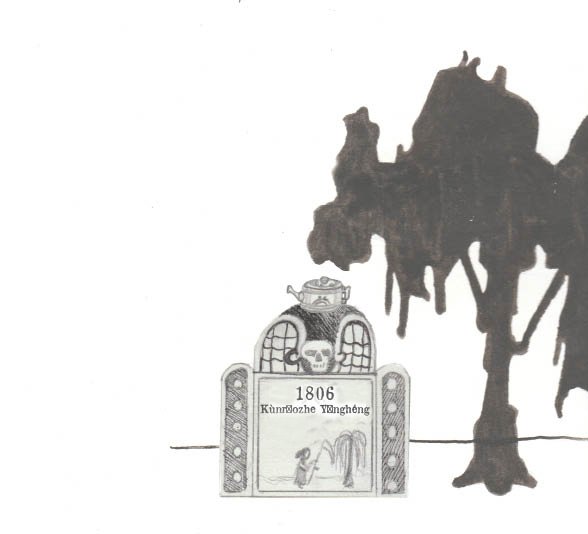

We make it past the regular throng of people trespassing on the widow’s wits. We make it to the back door from the carriage house. We are invited in for some fine tea that is poured from a unique tea pot. It was exquisite blue and white hand painted porcelain with a stout cylinder-like shape, rather than a more rounded one that came over with an obscure ancestor named Kùnrǎozhe Yǒnghéng from China. I think she mentioned it was during the time that the Salem was being attacked by Chinese Vampires who hid their horrid feeding habit amongst the hypodermic deaths from the opium users in Salem.

She pours out a fine Lapsang souchong and remembers I like plenty of milk in mine so she pours only a half cup for me. Louie drove away in a hurry and did not join us.

It is when Teddy burst in that I notice that there was a third teacup in which she already poured a full cup into. “I just got done with Taft and he is talking more and more of breaking my Square Deal. Frick has persuaded him too with the Tennessee Iron and Coal deal. The Republican Party is falling into Whigs’ and Tories’ hands more and more every day as England persuades those alumni from Yale to do so,” Teddy said as he sat heavy and almost knocked over his tea, “I apologize for the spill.”

“That is OK old friend. I will clean it up.”

“So what is going on at your estate at night. I have heard rumors,” Teddy asked with true concern hoping it was not as bad as he has surmised.

“Strange goings on. Evil things. I hear all sorts of howls that can not come from beast or humans of this world that crescendo at 3am. Many people and strange shadows do I see run past my windows. I have called in many of the larger men who worked in my late husband’s factory which he trusted with his life to protect me in the night. They stand guard at all the doors and most of the windows. During the night I am a prisoner on my own property within this house. Many Federal guards and those damn Pinkertons are about. Many have sexually accosted me on several occasions and said things by dear Robert would even blush at. He must be in a terrible fit looking down at me being powerless to help,” the widow said before continuing in a very disgusted tone, “I have even went down to the beach to see Taft in the nude under the moon, all 400 pounds of him. He had more rolls than the waves rolling in the sea. That image is burned into my mind forever and will haunt me beyond this life. You would not believe what young dames he had satisfying his whims at the same time. Truly horrid!!! He acts this way with his wife who still is catatonic.”

“Would you have a sample of his handwriting; maybe from his lease?” with that Teddy produced two pieces of paper, “Here this one is the letter Taft sent accepting the position I offered him as I became president in truth. This other one is a page ripped from Weishaupt’s manuscript, that Nikola mentioned seeing, signed by William Russell.”

Mrs. Evans returned with the lease and Teddy investigated the style of the hand. It was more like Russell’s than the writing on the letter Teddy kept always in his wallet. “Strange, it is Russell’s hand. How can this be?”

“Teddy, Ephraim Waite was said to posses his daughter Asenath who was stealing Edward Derby, her husband’s, mind and body. He was forced to occupy the dead corpse of her long enough to convince his friend to kill her in his own body. Maybe Ephraim jumped bodies before the body of Edward was finished; per say in even a cat?”

“I have heard of this Waite, but he was known as Arthur Edward Waite. He had the Ryder-Waite Tarot Deck made, but in secret attributed to his coven name Kamong. He had another deck made with the qlipothic tree that could work many horrid spells, open portals between places, and even undo creation,” I explained to him.

It was many years ago I hid some of the qlipothic stones under the Earth with the Dark Fairies on a remarkable All Hallows Eve.

“Now Taft’s father, Alphonso, started the Skull & Bones with Russell. Could Russell have taken over this Waite and in time made his way to his partner’s son as he was taking over the presidency? The Waites hailing out of Gloucester have spread all over the Gold Coast and hold much influence still. Some say a very dark fishy influence...” Teddy continued.

“I know in 1830 Russell went to meet Weishaupt upon his last days and brought back many secrets of the Illuminati he created. Did Russell have Weishaupt take over his mind and body? Maybe Russell fought like Edward Derby for three years before he had to let go. In 1833 Russell and Alphonso Taft make the Skull & Bones.” I wonder out loud.

Continued on the Last Story...

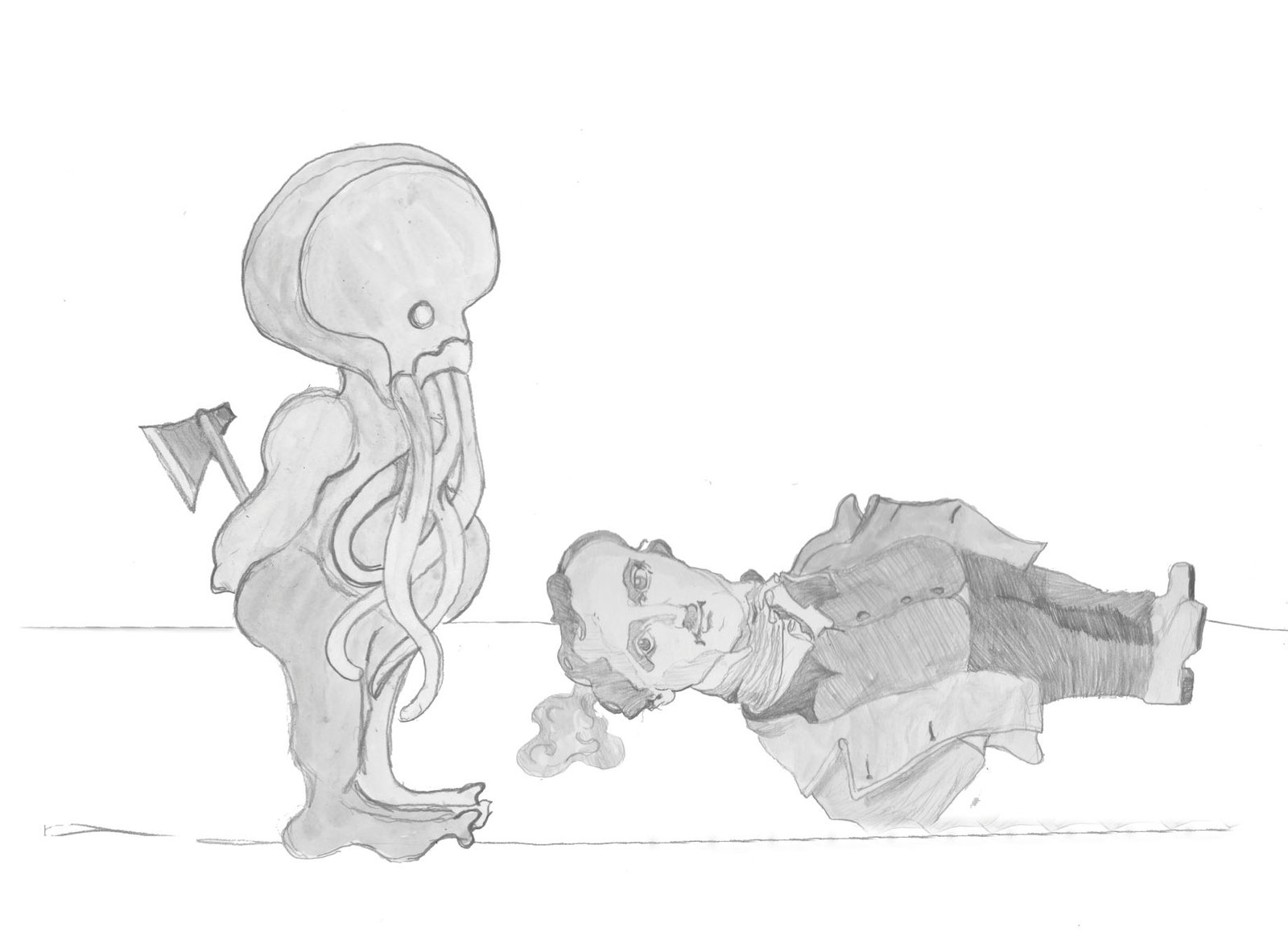

Now we have had a little taste of death with a dash of the occult. Skull & Bones and fast cars. Could Evans' fall from his horse have been murder? I have always said cars were safer than horses...as my friend below can attest to.

What about the possession of Edward Derby? How does that connect to one real obese president?

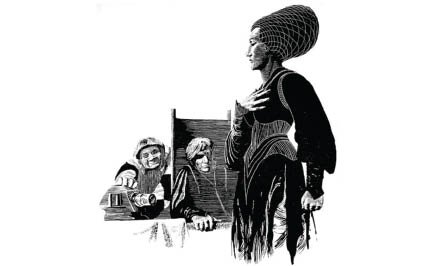

THE EYES HAVE IT

RANDALL GARRETT

Illustrated by John Schoenherr

In a sense, this is a story of here-and-now. This Earth, this year ... but on a history-line slipped slightly sidewise. A history in which a great man acted differently, and Magic, rather than physical science, was developed....

Sir Pierre Morlaix, Chevalier of the Angevin Empire, Knight of the Golden Leopard, and secretary-in-private to my lord, the Count D’Evreux, pushed back the lace at his cuff for a glance at his wrist watch--three minutes of seven. The Angelus had rung at six, as always, and my lord D’Evreux had been awakened by it, as always. At least, Sir Pierre could not remember any time in the past seventeen years when my lord had not awakened at the Angelus. Once, he recalled, the sacristan had failed to ring the bell, and the Count had been furious for a week. Only the intercession of Father Bright, backed by the Bishop himself, had saved the sacristan from doing a turn in the dungeons of Castle D’Evreux.

Sir Pierre stepped out into the corridor, walked along the carpeted flagstones, and cast a practiced eye around him as he walked. These old castles were difficult to keep clean, and my lord the Count was fussy about nitre collecting in the seams between the stones of the walls. All appeared quite in order, which was a good thing. My lord the Count had been making a night of it last evening, and that always made him the more peevish in the morning. Though he always woke at the Angelus, he did not always wake up sober.

Sir Pierre stopped before a heavy, polished, carved oak door, selected a key from one of the many at his belt, and turned it in the lock. Then he went into the elevator and the door locked automatically behind him. He pressed the switch and waited in patient silence as he was lifted up four floors to the Count’s personal suite.

By now, my lord the Count would have bathed, shaved, and dressed. He would also have poured down an eye-opener consisting of half a water glass of fine Champagne brandy. He would not eat breakfast until eight. The Count had no valet in the strict sense of the term. Sir Reginald Beauvay held that title, but he was never called upon to exercise the more personal functions of his office. The Count did not like to be seen until he was thoroughly presentable.

The elevator stopped. Sir Pierre stepped out into the corridor and walked along it toward the door at the far end. At exactly seven o’clock, he rapped briskly on the great door which bore the gilt-and-polychrome arms of the House D’Evreux.

For the first time in seventeen years, there was no answer.

Sir Pierre waited for the growled command to enter for a full minute, unable to believe his ears. Then, almost timidly, he rapped again.

There was still no answer.

Then, bracing himself for the verbal onslaught that would follow if he had erred, Sir Pierre turned the handle and opened the door just as if he had heard the Count’s voice telling him to come in.

“Good morning, my lord,” he said, as he always had for seventeen years.

But the room was empty, and there was no answer.

He looked around the huge room. The morning sunlight streamed in through the high mullioned windows and spread a diamond-checkered pattern across the tapestry on the far wall, lighting up the brilliant hunting scene in a blaze of color.

“My lord?”

Nothing. Not a sound.

The bedroom door was open. Sir Pierre walked across to it and looked in.

He saw immediately why my lord the Count had not answered, and that, indeed, he would never answer again.

My lord the Count lay flat on his back, his arms spread wide, his eyes staring at the ceiling. He was still clad in his gold and scarlet evening clothes. But the great stain on the front of his coat was not the same shade of scarlet as the rest of the cloth, and the stain had a bullet hole in its center.

Sir Pierre looked at him without moving for a long moment. Then he stepped over, knelt, and touched one of the Count’s hands with the back of his own. It was quite cool. He had been dead for hours.

“I knew someone would do you in sooner or later, my lord,” said Sir Pierre, almost regretfully.

Then he rose from his kneeling position and walked out without another look at his dead lord. He locked the door of the suite, pocketed the key, and went back downstairs in the elevator.

___

Mary, Lady Duncan stared out of the window at the morning sunlight and wondered what to do. The Angelus bell had awakened her from a fitful sleep in her chair, and she knew that, as a guest at Castle D’Evreux, she would be expected to appear at Mass again this morning. But how could she? How could she face the Sacramental Lord on the altar--to say nothing of taking the Blessed Sacrament itself. Still, it would look all the more conspicuous if she did not show up this morning after having made it a point to attend every morning with Lady Alice during the first four days of this visit.

She turned and glanced at the locked and barred door of the bedroom. He would not be expected to come. Laird Duncan used his wheelchair as an excuse, but since he had taken up black magic as a hobby he had, she suspected, been actually afraid to go anywhere near a church.

If only she hadn’t lied to him! But how could she have told the truth? That would have been worse--infinitely worse. And now, because of that lie, he was locked in his bedroom doing only God and the Devil knew what.

If only he would come out. If he would only stop whatever it was he had been doing for all these long hours--or at least finish it! Then they could leave Evreux, make some excuse--any excuse--to get away. One of them could feign sickness. Anything, anything to get them out of France, across the Channel, and back to Scotland, where they would be safe!

She looked back out of the window, across the courtyard, at the towering stone walls of the Great Keep and at the high window that opened into the suite of Edouard, Count D’Evreux.

Last night she had hated him, but no longer. Now there was only room in her heart for fear.

She buried her face in her hands and cursed herself for a fool. There were no tears left for weeping--not after the long night.

Behind her, she heard the sudden noise of the door being unlocked, and she turned.

Laird Duncan of Duncan opened the door and wheeled himself out. He was followed by a malodorous gust of vapor from the room he had just left. Lady Duncan stared at him.

He looked older than he had last night, more haggard and worn, and there was something in his eyes she did not like. For a moment he said nothing. Then he wet his lips with the tip of his tongue. When he spoke, his voice sounded dazed.

“There is nothing to fear any more,” he said. “Nothing to fear at all.”

___

The Reverend Father James Valois Bright, Vicar of the Chapel of Saint-Esprit, had as his flock the several hundred inhabitants of the Castle D’Evreux. As such, he was the ranking priest--socially, not hierarchically--in the country. Not counting the Bishop and the Chaplain at the Cathedral, of course. But such knowledge did little good for the Father’s peace of mind. The turnout of the flock was abominably small for its size--especially for week-day Masses. The Sunday Masses were well attended, of course; Count D’Evreux was there punctually at nine every Sunday, and he had a habit of counting the house. But he never showed up on weekdays, and his laxity had allowed a certain further laxity to filter down through the ranks.

The great consolation was Lady Alice D’Evreux. She was a plain, simple girl, nearly twenty years younger than her brother, the Count, and quite his opposite in every way. She was quiet where he was thundering, self-effacing where he was flamboyant, temperate where he was drunken, and chaste where he was--

Father Bright brought his thoughts to a full halt for a moment. He had, he reminded himself, no right to make judgments of that sort. He was not, after all, the Count’s confessor; the Bishop was. Besides, he should have his mind on his prayers just now.

He paused and was rather surprised to notice that he had already put on his alb, amice, and girdle, and he was aware that his lips had formed the words of the prayer as he had donned each of them.

Habit, he thought, can be destructive to the contemplative faculty.

He glanced around the sacristy. His server, the young son of the Count of Saint Brieuc, sent here to complete his education as a gentleman who would some day be the King’s Governor of one of the most important counties in Brittany, was pulling his surplice down over his head. The clock said 7:11.

Father Bright forced his mind Heavenward and repeated silently the vesting prayers that his lips had formed meaninglessly, this time putting his full intentions behind them. Then he added a short mental prayer asking God to forgive him for allowing his thoughts to stray in such a manner.

He opened his eyes and reached for his chasuble just as the sacristy door opened and Sir Pierre, the Count’s Privy Secretary, stepped in.

“I must speak to you, Father,” he said in a low voice. And, glancing at the young De Saint-Brieuc, he added: “Alone.”

Normally, Father Bright would have reprimanded anyone who presumed to break into the sacristy as he was vesting for Mass, but he knew that Sir Pierre would never interrupt without good reason. He nodded and went outside in the corridor that led to the altar.

“What is it, Pierre?” he asked.

“My lord the Count is dead. Murdered.”

After the first momentary shock, Father Bright realized that the news was not, after all, totally unexpected. Somewhere in the back of his mind, it seemed he had always known that the Count would die by violence long before debauchery ruined his health.

“Tell me about it,” he said quietly.

Sir Pierre reported exactly what he had done and what he had seen.

“Then I locked the door and came straight here,” he told the priest.

“Who else has the key to the Count’s suite?” Father Bright asked.

“No one but my lord himself,” Sir Pierre answered, “at least as far as I know.”

“Where is his key?”

“Still in the ring at his belt. I noticed that particularly.”

“Very good. We’ll leave it locked. You’re certain the body was cold?”

“Cold and waxy, Father.”

“Then he’s been dead many hours.”

“Lady Alice will have to be told,” Sir Pierre said.

Father Bright nodded. “Yes. The Countess D’Evreux must be informed of her succession to the County Seat.” He could tell by the sudden momentary blank look that came over Sir Pierre’s face that the Privy Secretary had not yet realized fully the implications of the Count’s death. “I’ll tell her, Pierre. She should be in her pew by now. Just step into the church and tell her quietly that I want to speak to her. Don’t tell her anything else.”

“I understand, Father,” said Sir Pierre.

___

There were only twenty-five or thirty people in the pews--most of them women--but Alice, Countess D’Evreux was not one of them. Sir Pierre walked quietly and unobtrusively down the side aisle and out into the narthex. She was standing there, just inside the main door, adjusting the black lace mantilla about her head, as though she had just come in from outside. Suddenly, Sir Pierre was very glad he would not have to be the one to break the news.

She looked rather sad, as always, her plain face unsmiling. The jutting nose and square chin which had given her brother the Count a look of aggressive handsomeness only made her look very solemn and rather sexless, although she had a magnificent figure.

“My lady,” Sir Pierre said, stepping towards her, “the Reverent Father would like to speak to you before Mass. He’s waiting at the sacristy door.”

She held her rosary clutched tightly to her breast and gasped. Then she said, “Oh. Sir Pierre. I’m sorry; you quite surprised me. I didn’t see you.”

“My apologies, my lady.”

“It’s all right. My thoughts were elsewhere. Will you take me to the good Father?”

Father Bright heard their footsteps coming down the corridor before he saw them. He was a little fidgety because Mass was already a minute overdue. It should have started promptly at 7:15.

The new Countess D’Evreux took the news calmly, as he had known she would. After a pause, she crossed herself and said, “May his soul rest in peace. I will leave everything in your hands, Father, Sir Pierre. What are we to do?”

“Pierre must get on the teleson to Rouen immediately and report the matter to His Highness. I will announce your brother’s death and ask for prayers for his soul--but I think I need say nothing about the manner of his death. There is no need to arouse any more speculation and fuss than necessary.”

“Very well,” said the Countess. “Come, Sir Pierre; I will speak to the Duke, my cousin, myself.”

“Yes, my lady.”

Father Bright returned to the sacristy, opened the missal, and changed the placement of the ribbons. Today was an ordinary Feria; a Votive Mass would not be forbidden by the rubics. The clock said 7:17.

He turned to young De Saint-Brieuc, who was waiting respectfully. “Quickly, my son--go and get the unbleached beeswax candles and put them on the altar. Be sure you light them before you put out the white ones. Hurry, now; I will be ready by the time you come back. Oh yes--and change the altar frontal. Put on the black.”

“Yes, Father.” And the lad was gone.

Father Bright folded the green chasuble and returned it to the drawer, then took out the black one. He would say a Requiem for the Souls of All the Faithful Departed--and hope that the Count was among them.

___

His Royal Highness, the Duke of Normandy, looked over the official letter his secretary had just typed for him. It was addressed to Serenissimus Dominus Nostrus Iohannes Quartus, Dei Gratia, Angliae, Franciae, Scotiae, Hiberniae, et Novae Angliae, Rex, Imperator, Fidei Defensor, ... “Our Most Serene Lord, John IV, by the Grace of God King and Emperor of England, France, Scotland, Ireland, and New England, Defender of the Faith, ...”

It was a routine matter; simple notification to his brother, the King, that His Majesty’s most faithful servant, Edouard, Count of Evreux had departed this life, and asking His Majesty’s confirmation of the Count’s heir-at-law, Alice, Countess of Evreux as his lawful successor.

His Highness finished reading, nodded, and scrawled his signature at the bottom: Richard Dux Normaniae.

Then, on a separate piece of paper, he wrote: “Dear John, May I suggest you hold up on this for a while? Edouard was a lecher and a slob, and I have no doubt he got everything he deserved, but we have no notion who killed him. For any evidence I have to the contrary, it might have been Alice who pulled the trigger. I will send you full particulars as soon as I have them. With much love, Your brother and servant, Richard.”

He put both papers into a prepared envelope and sealed it. He wished he could have called the king on the teleson, but no one had yet figured out how to get the wires across the channel.

He looked absently at the sealed envelope, his handsome blond features thoughtful. The House of Plantagenet had endured for eight centuries, and the blood of Henry of Anjou ran thin in its veins, but the Norman strain was as strong as ever, having been replenished over the centuries by fresh infusions from Norwegian and Danish princesses. Richard’s mother, Queen Helga, wife to His late Majesty, Henry X, spoke very few words of Anglo-French, and those with a heavy Norse accent.

Nevertheless, there was nothing Scandinavian in the language, manner, or bearing of Richard, Duke of Normandy. Not only was he a member of the oldest and most powerful ruling family of Europe, but he bore a Christian name that was distinguished even in that family. Seven Kings of the Empire had borne the name, and most of them had been good Kings--if not always “good” men in the nicey-nicey sense of the word. Even old Richard I, who’d been pretty wild during the first forty-odd years of his life, had settled down to do a magnificent job of kinging for the next twenty years. The long and painful recovery from the wound he’d received at the Siege of Chaluz had made a change in him for the better.

There was a chance that Duke Richard might be called upon to uphold the honor of that name as King. By law, Parliament must elect a Plantagenet as King in the event of the death of the present Sovereign, and while the election of one of the King’s two sons, the Prince of Wales and the Duke of Lancaster, was more likely than the election of Richard, he was certainly not eliminated from the succession.

Meantime, he would uphold the honor of his name as Duke of Normandy.

Murder had been done; therefore justice must be done. The Count D’Evreux had been known for his stern but fair justice, almost as well as he had been known for his profligacy. And, just as his pleasures had been without temperance, so his justice had been untempered by mercy. Whoever had killed him would find both justice and mercy--in so far as Richard had it within his power to give it.

Although he did not formulate it in so many words, even mentally, Richard was of the opinion that some debauched woman or cuckolded man had fired the fatal shot. Thus he found himself inclining toward mercy before he knew anything substantial about the case at all.

Richard dropped the letter he was holding into the special mail pouch that would be placed aboard the evening trans-channel packet, and then turned in his chair to look at the lean, middle-aged man working at a desk across the room.

“My lord Marquis,” he said thoughtfully.

“Yes, Your Highness?” said the Marquis of Rouen, looking up.

“How true are the stories one has heard about the late Count?”

“True, Your Highness?” the Marquis said thoughtfully. “I would hesitate to make any estimate of percentages. Once a man gets a reputation like that, the number of his reputed sins quickly surpasses the number of actual ones. Doubtless many of the stories one hears are of whole cloth; others may have only a slight basis in fact. On the other hand, it is highly likely that there are many of which we have never heard. It is absolutely certain, however, that he has acknowledged seven illegitimate sons, and I dare say he has ignored a few daughters--and these, mind you, with unmarried women. His adulteries would be rather more difficult to establish, but I think your Highness can take it for granted that such escapades were far from uncommon.”

He cleared his throat and then added, “If Your Highness is looking for motive, I fear there is a superabundance of persons with motive.”

“I see,” the Duke said. “Well, we will wait and see what sort of information Lord Darcy comes up with.” He looked up at the clock. “They should be there by now.”

Then, as if brushing further thoughts on the subject from his mind, he went back to work, picking up a new sheaf of state papers from his desk.

The Marquis watched him for a moment and smiled a little to himself. The young Duke took his work seriously, but was well-balanced about it. A little inclined to be romantic--but aren’t we all at nineteen? There was no doubt of his ability, nor of his nobility. The Royal Blood of England always came through.

___

“My lady,” said Sir Pierre gently, “the Duke’s Investigators have arrived.”

My Lady Alice, Countess D’Evreux, was seated in a gold-brocade upholstered chair in the small receiving room off the Great Hall. Standing near her, looking very grave, was Father Bright. Against the blaze of color on the walls of the room, the two of them stood out like ink blots. Father Bright wore his normal clerical black, unrelieved except for the pure white lace at collar and cuffs. The Countess wore unadorned black velvet, a dress which she had had to have altered hurriedly by her dressmaker; she had always hated black and owned only the mourning she had worn when her mother died eight years before. The somber looks on their faces seemed to make the black blacker.

“Show them in, Sir Pierre,” the Countess said calmly.

Sir Pierre opened the door wider and three men entered. One was dressed as one gently born, the other two wore the livery of the Duke of Normandy.

The gentleman bowed. “I am Lord Darcy, Chief Criminal Investigator for His Highness, the Duke, and your servant, my lady.” He was a tall, brown-haired man in his thirties with a rather handsome, lean face. He spoke Anglo-French with a definite English accent.

“My pleasure, Lord Darcy,” said the Countess. “This is our vicar, Father Bright.”

“Your servant, Reverend Sir.” Then he presented the two men with him. The first was a scholarly-looking, graying man wearing pince-nez glasses with gold rims, Dr. Pateley, Physician. The second, a tubby, red-faced, smiling man, was Master Sean O Lochlainn, Sorcerer.

As soon as Master Sean was presented he removed a small, leather-bound folder from his belt pouch and proffered it to the priest. “My license, Reverend Father.”

Father Bright took it and glanced over it. It was the usual thing, signed and sealed by the Archbishop of Rouen. The law was rather strict on that point; no sorcerer could practice without the permission of the Church, and a license was given only after careful examination for orthodoxy of practice.

“It seems to be quite in order, Master Sean,” said the priest, handing the folder back. The tubby little sorcerer bowed his thanks and returned the folder to his belt pouch.

Lord Darcy had a notebook in his hand. “Now, unpleasant as it may be, we shall have to check on a few facts.” He consulted his notes, then looked up at Sir Pierre. “You, I believe, discovered the body?”

“That is correct, your lordship.”

“How long ago was this?”

Sir Pierre glanced at his wrist watch. It was 9:55. “Not quite three hours ago, your lordship.”

“At what time, precisely?”

“I rapped on the door precisely at seven, and went in a minute or two later--say 7:01 or 7:02.”

“How do you know the time so exactly?”

“My lord the Count,” said Sir Pierre with some stiffness, “insisted upon exact punctuality. I have formed the habit of referring to my watch regularly.”

“I see. Very good. Now, what did you do then?”

Sir Pierre described his actions briefly.

“The door to his suite was not locked, then?” Lord Darcy asked.

“No, sir.”

“You did not expect it to be locked?”

“No, sir. It has not been for seventeen years.”

Lord Darcy raised one eyebrow in a polite query. “Never?”

“Not at seven o’clock, your lordship. My lord the Count always rose promptly at six and unlocked the door before seven.”

“He did lock it at night, then?”

“Yes, sir.”

Lord Darcy looked thoughtful and made a note, but he said nothing more on that subject. “When you left, you locked the door?”

“That is correct, your lordship.”

“And it has remained locked ever since?”

Sir Pierce hesitated and glanced at Father Bright. The priest said: “At 8:15, Sir Pierre and I went in. I wished to view the body. We touched nothing. We left at 8:20.”

Master Sean O Lochlainn looked agitated. “Er ... excuse me, Reverend Sir. You didn’t give him Holy Unction, I hope?”

“No,” said Father Bright. “I thought it would be better to delay that until after the authorities has seen the ... er ... scene of the crime. I wouldn’t want to make the gathering of evidence any more difficult than necessary.”

“Quite right,” murmured Lord Darcy.

“No blessings, I trust, Reverend Sir?” Master Sean persisted. “No exorcisms or--”

“Nothing,” Father Bright interrupted somewhat testily. “I believe I crossed myself when I saw the body, but nothing more.”

“Crossed yourself, sir. Nothing else?”

“No.”

“Well, that’s all right, then. Sorry to be so persistent, Reverend Sir, but any miasma of evil that may be left around is a very important clue, and it shouldn’t be dispersed until it’s been checked, you see.”

“Evil?” My lady the Countess looked shocked.

“Sorry, my lady, but--” Master Sean began contritely.

But Father Bright interrupted by speaking to the Countess. “Don’t distress yourself, my daughter; these men are only doing their duty.”

“Of course. I understand. It’s just that it’s so--” She shuddered delicately.

Lord Darcy cast Master Sean a warning look, then asked politely, “Has my lady seen the deceased?”

“No,” she said. “I will, however, if you wish.”

“We’ll see,” said Lord Darcy. “Perhaps it won’t be necessary. May we go up to the suite now?”

“Certainly,” the Countess said. “Sir Pierre, if you will?”

“Yes, my lady.”

As Sir Pierre unlocked the emblazoned door, Lord Darcy said: “Who else sleeps on this floor?”

“No one else, your lordship,” Sir Pierre said. “The entire floor is ... was ... reserved for my lord the Count.”

“Is there any way up besides that elevator?”

Sir Pierre turned and pointed toward the other end of the short hallway. “That leads to the staircase,” he said, pointing to a massive oaken door, “but it’s kept locked at all times. And, as you can see, there is a heavy bar across it. Except for moving furniture in and out or something like that, it’s never used.”

“No other way up or down, then?”

Sir Pierre hesitated. “Well, yes, your lordship, there is. I’ll show you.”

“A secret stairway?”

“Yes, your lordship.”

“Very well. We’ll look at it after we’ve seen the body.”

Lord Darcy, having spent an hour on the train down from Rouen, was anxious to see the cause of the trouble at last.

He lay in the bedroom, just as Sir Pierre and Father Bright had left him.

“If you please, Dr. Pateley,” said his lordship.

He knelt on one side of the corpse and watched carefully while Pateley knelt on the other side and looked at the face of the dead man. Then he touched one of the hands and tried to move an arm. “Rigor has set in--even to the fingers. Single bullet hole. Rather small caliber--I should say a .28 or .34--hard to tell until I’ve probed out the bullet. Looks like it went right through the heart, though. Hard to tell about powder burns; the blood has soaked the clothing and dried. Still, these specks ... hm-m-m. Yes. Hm-m-m.”

Lord Darcy’s eyes took in everything, but there was little enough to see on the body itself. Then his eye was caught by something that gave off a golden gleam. He stood up and walked over to the great canopied four-poster bed, then he was on his knees again, peering under it. A coin? No.

He picked it up carefully and looked at it. A button. Gold, intricately engraved in an Arabesque pattern, and set in the center with a single diamond. How long had it lain there? Where had it come from? Not from the Count’s clothing, for his buttons were smaller, engraved with his arms, and had no gems. Had a man or a woman dropped it? There was no way of knowing at this stage of the game.

Darcy turned to Sir Pierre. “When was this room last cleaned?”

“Last evening, your lordship,” the secretary said promptly. “My lord was always particular about that. The suite was always to be swept and cleaned during the dinner hour.”

“Then this must have rolled under the bed at some time after dinner. Do you recognize it? The design is distinctive.”

The Privy Secretary looked carefully at the button in the palm of Lord Darcy’s hand without touching it. “I ... I hesitate to say,” he said at last. “It looks like ... but I’m not sure--”

“Come, come, Chevalier! Where do you think you might have seen it? Or one like it.” There was a sharpness in the tone of his voice.

“I’m not trying to conceal anything, your lordship,” Sir Pierre said with equal sharpness. “I said I was not sure. I still am not, but it can be checked easily enough. If your lordship will permit me--” He turned and spoke to Dr. Pateley, who was still kneeling by the body. “May I have my lord the Count’s keys, doctor?”

Pateley glanced up at Lord Darcy, who nodded silently. The physician detached the keys from the belt and handed them to Sir Pierre.

The Privy Secretary looked at them for a moment, then selected a small gold key. “This is it,” he said, separating it from the others on the ring. “Come with me, your lordship.”

___

Darcy followed him across the room to a broad wall covered with a great tapestry that must have dated back to the sixteenth century. Sir Pierre reached behind it and pulled a cord. The entire tapestry slid aside like a panel, and Lord Darcy saw that it was supported on a track some ten feet from the floor. Behind it was what looked at first like ordinary oak paneling, but Sir Pierre fitted the small key into an inconspicuous hole and turned. Or, rather, tried to turn.

“That’s odd,” said Sir Pierre. “It’s not locked!”

He took the key out and pressed on the panel, shoving sideways with his hand to move it aside. It slid open to reveal a closet.

The closet was filled with women’s clothing of all kinds, and styles.

Lord Darcy whistled soundlessly.

“Try that blue robe, your lordship,” the Privy Secretary said. “The one with the--Yes, that’s the one.”

Lord Darcy took it off its hanger. The same buttons. They matched. And there was one missing from the front! Torn off! “Master Sean!” he called without turning.

Master Sean came with a rolling walk. He was holding an oddly-shaped bronze thing in his hand that Sir Pierre didn’t quite recognize. The sorcerer was muttering. “Evil, that there is! Faith, and the vibrations are all over the place. Yes, my lord?”

“Check this dress and the button when you get round to it. I want to know when the two parted company.”

“Yes, my lord.” He draped the robe over one arm and dropped the button into a pouch at his belt. “I can tell you one thing, my lord. You talk about an evil miasma, this room has got it!” He held up the object in his hand. “There’s an underlying background--something that has been here for years, just seeping in. But on top of that, there’s a hellish big blast of it superimposed. Fresh it is, and very strong.”

“I shouldn’t be surprised, considering there was murder done here last night--or very early this morning,” said Lord Darcy.

“Hm-m-m, yes. Yes, my lord, the death is there--but there’s something else. Something I can’t place.”

“You can tell that just by holding that bronze cross in your hand?” Sir Pierre asked interestedly.

Master Sean gave him a friendly scowl. “’Tisn’t quite a cross, sir. This is what is known as a crux ansata. The ancient Egyptians called it an ankh. Notice the loop at the top instead of the straight piece your true cross has. Now, your true cross--if it were properly energized, blessed, d’ye see--your true cross would tend to dissipate the evil. The ankh merely vibrates to evil because of the closed loop at the top, which makes a return circuit. And it’s not energized by blessing, but by another ... um ... spell.”

“Master Sean, we have a murder to investigate,” said Lord Darcy.

The sorcerer caught the tone of his voice and nodded quickly. “Yes, my lord.” And he walked rollingly away.

“Now where’s that secret stairway you mentioned, Sir Pierre?” Lord Darcy asked.

“This way, your lordship.”

He led Lord Darcy to a wall at right angles to the outer wall and slid back another tapestry.

“Good Heavens,” Darcy muttered, “does he have something concealed behind every arras in the place?” But he didn’t say it loud enough for the Privy Secretary to hear.

___

This time, what greeted them was a solid-seeming stone wall. But Sir Pierre pressed in on one small stone, and a section of the wall swung back, exposing a stairway.

“Oh, yes,” Darcy said. “I see what he did. This is the old spiral stairway that goes round the inside of the Keep. There are two doorways at the bottom. One opens into the courtyard, the other is a postern gate through the curtain wall to the outside--but that was closed up in the sixteenth century, so the only way out is into the courtyard.”

“Your lordship knows Castle D’Evreux, then?” Sir Pierre said. The knight himself was nearly fifty, while Darcy was only in his thirties, and Sir Pierre had no recollection of Darcy’s having been in the castle before.

“Only by the plans in the Royal Archives. But I have made it a point to--” He stopped. “Dear me,” he interrupted himself mildly, “what is that?”

“That” was something that had been hidden by the arras until Sir Pierre had slid it aside and was still showing only a part of itself. It lay on the floor a foot or so from the secret door.

Darcy knelt down and pulled the tapestry back from the object. “Well, well. A .28 two-shot pocket gun. Gold-chased, beautifully engraved, mother-of-pearl handle. A regular gem.” He picked it up and examined it closely. “One shot fired.”

He stood up and showed it to Sir Pierre. “Ever see it before?”

The Privy Secretary looked at the weapon closely. Then he shook his head. “Not that I recall, your lordship. It certainly isn’t one of the Count’s guns.”

“You’re certain?”

“Quite certain, your lordship. I’ll show you the gun collection if you want. My lord the Count didn’t like tiny guns like that; he preferred a larger caliber. He would never have owned what he considered a toy.”

“Well, we’ll have to look into it.” He called over Master Sean again and gave the gun into his keeping. “And keep your eyes open for anything else of interest, Master Sean. So far, everything of interest besides the late Count himself has been hiding under beds or behind arrases. Check everything. Sir Pierre and I are going for a look down this stairway.”

The stairway was gloomy, but enough light came in through the arrow slits spaced at intervals along the outer way to illuminate the interior. It spiraled down between the inner and outer walls of the Great Keep, making four complete circuits before it reached ground level. Lord Darcy looked carefully at the steps, the walls, and even the low, arched overhead as he and Sir Pierre went down.

After the first circuit, on the floor beneath the Count’s suite, he stopped. “There was a door here,” he said, pointing to a rectangular area in the inner wall.

“Yes, your lordship. There used to be an opening at every floor, but they were all sealed off. It’s quite solid, as you can see.”

“Where would they lead if they were open?”

“The county offices. My own office, the clerk’s offices, the constabulary on the first floor. Below are the dungeons. My lord the Count was the only one who lived in the Keep itself. The rest of the household live above the Great Hall.”

“What about guests?”

“They’re usually housed in the east wing. We only have two house guests at the moment. Laird and Lady Duncan have been with us for four days.”

“I see.” They went down perhaps four more steps before Lord Darcy asked quietly, “Tell me, Sir Pierre, were you privy to all of Count D’Evreux’s business?”

Another four steps down before Sir Pierre answered. “I understand what your lordship means,” he said. Another two steps. “No, I was not. I was aware that my lord the Count engaged in certain ... er ... shall we say, liaisons with members of the opposite sex. However--”

He paused, and in the gloom, Lord Darcy could see his lips tighten. “However,” he continued, “I did not procure for my lord, if that is what you’re driving at. I am not and never have been a pimp.”

“I didn’t intend to suggest that you had, good knight,” said Lord Darcy in a tone that strongly implied that the thought had actually never crossed his mind. “Not at all. But certainly there is a difference between ‘aiding and abetting’ and simple knowledge of what is going on.”

“Oh. Yes. Yes, of course. Well, one cannot, of course, be the secretary-in-private of a gentleman such as my lord the Count for seventeen years without knowing something of what is going on, you’re right. Yes. Yes. Hm-m-m.”

Lord Darcy smiled to himself. Not until this moment had Sir Pierre realized how much he actually did know. In loyalty to his lord, he had literally kept his eyes shut for seventeen years.

“I realize,” Lord Darcy said smoothly, “that a gentleman would never implicate a lady nor besmirch the reputation of another gentleman without due cause and careful consideration. However,”--like the knight, he paused a moment before going on--”although we are aware that he was not discreet, was he particular?”

“If you mean by that, did he confine his attentions to those of gentle birth, your lordship, then I can say, no he did not. If you mean did he confine his attentions to the gentler sex, then I can only say that, as far as I know, he did.”

“I see. That explains the closet full of clothes.”

“Beg pardon, your lordship?”

“I mean that if a girl or woman of the lower classes were to come here, he would have proper clothing for them to wear--in spite of the sumptuary laws to the contrary.”

“Quite likely, your lordship. He was most particular about clothing. Couldn’t stand a woman who was sloppily dressed or poorly dressed.”

“In what way?”

“Well. Well, for instance, I recall once that he saw a very pretty peasant girl. She was dressed in the common style, of course, but she was dressed neatly and prettily. My lord took a fancy to her. He said, ‘Now there’s a lass who knows how to wear clothes. Put her in decent apparel, and she’d pass for a princess.’ But a girl, who had a pretty face and a fine figure, made no impression on him unless she wore her clothing well, if you see what I mean, your lordship.”

“Did you ever know him to fancy a girl who dressed in an offhand manner?” Lord Darcy asked.

“Only among the gently born, your lordship. He’d say, ‘Look at Lady So-and-so! Nice wench, if she’d let me teach her how to dress.’ You might say, your lordship, that a woman could be dressed commonly or sloppily, but not both.”

“Judging by the stuff in that closet,” Lord Darcy said, “I should say that the late Count had excellent taste in feminine dress.”

Sir Pierre considered. “Hm-m-m. Well, now, I wouldn’t exactly say so, your lordship. He knew how clothes should be worn, yes. But he couldn’t pick out a woman’s gown of his own accord. He could choose his own clothing with impeccable taste, but he’d not any real notion of how a woman’s clothing should go, if you see what I mean. All he knew was how good clothing should be worn. But he knew nothing about design for women’s clothing.”

“Then how did he get that closet full of clothes?” Lord Darcy asked, puzzled.

Sir Pierre chuckled. “Very simply, your lordship. He knew that the Lady Alice had good taste, so he secretly instructed that each piece that Lady Alice ordered should be made in duplicate. With small variations, of course. I’m certain my lady wouldn’t like it if she knew.”

“I dare say not,” said Lord Darcy thoughtfully.

“Here is the door to the courtyard,” said Sir Pierre. “I doubt that it has been opened in broad daylight for many years.” He selected a key from the ring of the late Count and inserted it into the keyhole. The door swung back, revealing a large crucifix attached to its outer surface. Lord Darcy crossed himself. “Lord in Heaven,” he said softly, “what is this?”

He looked out into a small shrine. It was walled off from the courtyard and had a single small entrance some ten feet from the doorway. There were four prie-dieus--small kneeling benches--arranged in front of the doorway.

“If I may explain, your lordship--” Sir Pierre began.

“No need to,” Lord Darcy said in a hard voice. “It’s rather obvious. My lord the Count was quite ingenious. This is a relatively newly-built shrine. Four walls and a crucifix against the castle wall. Anyone could come in here, day or night, for prayer. No one who came in would be suspected.” He stepped out into the small enclosure and swung around to look at the door. “And when that door is closed, there is no sign that there is a door behind the crucifix. If a woman came in here, it would be assumed that she came for prayer. But if she knew of that door--” His voice trailed off.

“Yes, your lordship,” said Sir Pierre. “I did not approve, but I was in no position to disapprove.”

“I understand.” Lord Darcy stepped out to the doorway of the little shrine and took a quick glance about. “Then anyone within the castle walls could come in here,” he said.

“Yes, your lordship.”

“Very well. Let’s go back up.”

___

In the small office which Lord Darcy and his staff had been assigned while conducting the investigation, three men watched while a fourth conducted a demonstration on a table in the center of the room.

Master Sean O Lochlainn held up an intricately engraved gold button with an Arabesque pattern and a diamond set in the center.

He looked at the other three. “Now, my lord, your Reverence, and colleague Doctor, I call your attention to this button.”

Dr. Pateley smiled and Father Bright looked stern. Lord Darcy merely stuffed tobacco--imported from the southern New England counties on the Gulf--into a German-made porcelain pipe. He allowed Master Sean a certain amount of flamboyance; good sorcerers were hard to come by.

“Will you hold the robe, Dr. Pateley? Thank you. Now, stand back. That’s it. Thank you. Now, I place the button on the table, a good ten feet from the robe.” Then he muttered something under his breath and dusted a bit of powder on the button. He made a few passes over it with his hands, paused, and looked up at Father Bright. “If you will, Reverend Sir?”

Father Bright solemnly raised his right hand, and, as he made the Sign of the Cross, said: “May this demonstration, O God, be in strict accord with the truth, and may the Evil One not in any way deceive us who are witnesses thereto. In the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.”

“Amen,” the other three chorused.

Master Sean crossed himself, then muttered something under his breath.

The button leaped from the table, slammed itself against the robe which Dr. Pateley held before him, and stuck there as though it had been sewn on by an expert.

“Ha!” said Master Sean. “As I thought!” He gave the other three men a broad, beaming smile. “The two were definitely connected!”

Lord Darcy looked bored. “Time?” he asked.

“In a moment, my lord,” Master Sean said apologetically. “In a moment.” While the other three watched, the sorcerer went through more spells with the button and the robe, although none were quite so spectacular as the first demonstration. Finally, Master Sean said: “About eleven thirty last night they were torn apart, my lord. But I shouldn’t like to make it any more definite than to say between eleven and midnight. The speed with which it returned to its place shows that it was ripped off very rapidly, however.”

“Very good,” said Lord Darcy. “Now the bullet, if you please.”